Published in The Clarity Journal 76 – 2018

By Neil James and Susan Kleimann

No one could object to the evaluation of texts to assess their quality and effectiveness. Many evaluation methods exist, from readability formulas and expert reviews to usability tests and the analysis of outcomes.

Yet in recent years, a divide has developed between practitioners who prefer one evaluation method over another. This preference often emerges from the types of documents each works with. Writers of an internal policy or submission in a government agency, for example, are more likely to review their draft against a checklist or with a colleague. The team designing and writing a standard tax form for the public are more likely to prefer large-scale usability testing.

Unfortunately, these differences in context have often led to debates about the relative value of one or another method. The value is often seen on a linear scale where some methods are “simpler” and implicitly less effective than the more “complex” alternatives higher up the scale.

1. A spectrum of methods

We decided to approach evaluation by looking equally at all the available methods to assess where each would best add value and in what context. We were then able to group them into 3 broad categories depending on their focus:

- text focus

- user focus

- outcomes focus.

As Figure 1 shows, we felt it was more useful to think of these as falling on a circular spectrum rather than a linear scale.

Figure 1: Spectrum of evaluation methods

Dr Neil James is Executive Director of the Plain English Foundation in Australia, which combines plain English training, editing and evaluation with a campaign for more ethical public language. Neil has pub- lished three books and over 90 articles and essays on language and literature. He is a regular speaker about language in the media throughout Australia. From 2008 to 2015, he chaired the International Plain Lan- guage Working Group and in 2015 became President of the Plain Language Associa- tion International (PLAIN).

Our concept of a spectrum builds on previous work by Janice Redish and Karen Schriver. Decades ago, Schriver mapped the ‘continuum’ of text-focused to reader- focused methods and concluded that “reader-focused methods are preferable”. Redish outlined the available range of outcome measures that can demonstrate value in a communication project.

We wanted to bring all of these methods into a single framework that would be practical to apply. But we also wanted to consider the value of each method in different contexts to determine how to select the right mix and scale of evaluation.

But first, let’s look at a high level at each of these methods on the spectrum.

TEXT FOCUS

A text-focused evaluation assesses characteristics in a text itself. Some of these relate to the “micro” features of vocabulary or syntax, such as the average:

- number of words in sentences

- number of syllables in words

- ratio of “difficult” words

- ratio of active to passive voice.

Some text-focused methods, such as readability formulas, can be applied in an

automated way through computer software. These can be particularly attractive in a professional context, as they imply a level of objectivity and do not require expertise to interpret a result in the broader context of the communication.

Other text criteria add macro elements such as:

- clarity of purpose

- length of paragraphs

- appropriate level of detail

- suitability of structure

- use of headings and other design features.

These “macro” elements more often require human judgement to assess how well

particular features will contribute to clarity, logic and cohesion. To evaluate these, a human reviewer may assess a written text against a checklist or a complex standard. When that reviewer is a communication specialist, they may also analyse audience needs in a formal way, and will bring valuable professional judgement to the task.

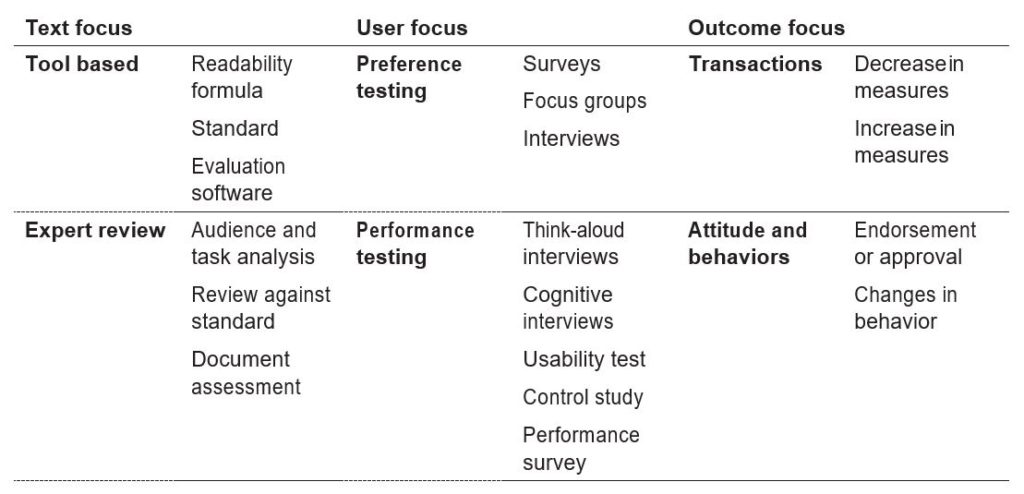

Figure 2: Text focus evaluation methods

| Tool-based | Expert review |

| Readability formulas | Audience and task analysis |

| Standard | Review against a standard |

| Evaluation software | Document assessment |

USER FOCUS

The next group of methods has emerged from fields such as marketing, cognitive psychology, and usability. These focus on the end user’s interaction with the text.

Marketing relies on revealing the preference of a potential consumer about a product, even when that product is a text. This can include questions about the elements assessed in broader textual evaluation, such as the structure, language, and design. But it can also probe the content and message in more detail.

Such preference testing provides qualitative information on what readers say they like and how they may react to a communication. It can be done online, through focus groups, or in single interviews.

On the other hand, performance testing determines how a reader actually interacts with a document – what they read, what they skip, how well they retain information, or even how well they complete an action or follow directions. Some performance tests can be as simple as asking someone to read a text and then answer a series of content questions. At other times, the test simulates a real-world situation to see if a reader can synthesize information and make a sophisticated judgement.

Figure 3: User focus evaluation methods

| Preference testing | Performance testing |

| Surveys | Think-aloud interviews |

| Focus groups | Cognitive interviews |

| Interviews | Usability testing |

| Controlled study | |

| Performance survey |

OUTCOMES FOCUS

The evaluation methods we’ve considered so far are generally applied before a document is released to its readers. Outcomes focused methods review the impact the document has once it has been used.

Some outcome evaluation is purely quantitative, such as whether measurable transactions have changed. These can include the number of phone calls received, the revenue raised, or the error rates experienced in response to a communication. Many of these methods are used to validate earlier evaluation methods and measure the relative effectiveness of different approaches to a communication.

Other outcomes evaluation is more qualitative, measuring attitudes and behaviors. In simple internal documents like memos or submissions, for example, one outcome measure is the response of decision makers, such as senior executives. In the corporate sector, qualitative outcomes might relate to the perception of a brand. In public health campaigns, it might assess the likelihood that people will change behaviors, such as toward healthier eating.

These evaluation methods can then influence how a document is revised if it is in ongoing use. When a document is used only once, outcomes evaluation may only influence other similar documents in the future.

Figure 4: Outcome focus evaluation methods

| Transactions | Attitudes and behaviors |

| Errors | Endorsement |

| Phone calls | Approval |

| Revenue | Changes in behavior |

While it is one thing to set out all of the available evaluation methods, there is currently no systematic framework to help practitioners choose the best method or mix of methods in a given context. So we decided to draft one.

1. The Kleimann-James evaluation framework

Our framework comes in two parts:

- an integrated table of evaluation methods

- a set of criteria to assess communication and business requirements.

By applying the criteria to a given context, the framework helps to judge which

evaluation methods will be most effective. Following is the integrated table of all the methods we’ve discussed so far.

Figure 5: Integrated table of evaluation methods

The first point we make is that this evaluation process is blended and scalable. It is not about selecting one method for each context, but considering a mix of two, three, or even more.

More importantly, each method can be applied at a simple or more complex scale. For example, a text-based evaluation may involve a single calculation for readability or a more comprehensive assessment using a range of criteria at micro and macro levels. Similarly, a performance test could evaluate a document with one to three cognitive interviews or could scale up to dozens of people across multiple locations.

In most cases, the best approach will blend several methods at different scales to maximise the insight gathered and validate the results between them. The key is not to be limited by one approach in evaluation practice, but to master the broadest range of methods and choose carefully case by case.

But what criteria should you apply in making this choice, and can you approach this in a structured way? This is the second part of the Kleimann-James framework.

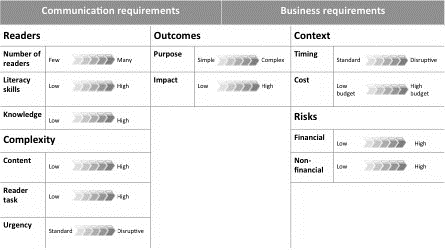

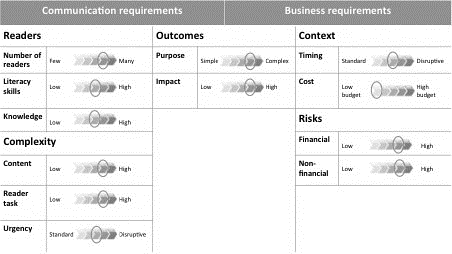

We started by considering three broad requirements: communication and business requirements, which overlap in the shared outcomes for a communication, as Figure 6 shows.

Figure 6: Requirements and outcomes

Using that concept, we developed a set of criteria in five areas that can help to select the best blend and scale of evaluation methods in a given context:

- Readers

- Complexity

- Outcomes

- Context

- Risks

Here’s how this came together in our framework.

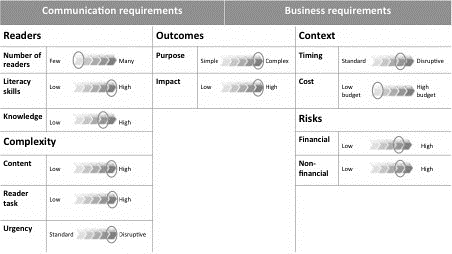

Figure 7: Criteria to select evaluation methods

As Figure 7 shows, the Reader and Complexity criteria are part of the communication requirements, while Context and Risks fall under business requirements. Outcomes bridge the two kinds of requirements because they relate to both.

The idea is that by reviewing each of these criteria in a context, we can better judge the right blend and scale of evaluation methods that will maximize the result. We’ll illustrate this with some examples, but first let’s look more closely at what we mean by each of these criteria.

READERS

There are three aspects to review with the intended audience:

- number of readers

- literacy skills

- knowledge of the topic.

A document for a single reader or few readers is likely to need only a text-based evaluation. But if those few readers have low literacy skills or topic knowledge, then it may call for a comprehensive form of text-based evaluation or an expert review. Even where those readers have extensive content knowledge, if their literacy is low the evaluation may need to be scaled up to ensure the communication will succeed.

Conversely, if a text is going to be read by thousands of people, a user-focused regime may be essential, even if the readers have high literacy and reasonable knowledge of the subject.

COMPLEXITY

The complexity of the material itself will also influence evaluation. Buying a house, for example, is a highly complex transaction in many countries, and one that few readers do frequently. It can whip up a storm of financial information.

At other times, the content may be relatively simple, such as the criteria for an insurance claim (let’s say for a robbery). But the task involved may be complex, requiring readers to fill out a complex form and provide a wide range of supporting documents.

Weighed against these two aspects of complexity is the urgency of a task. Many communications run along a predictable timeline. Income tax information, for example, comes at the same time each year. Company reports to shareholders have a set season around the mandated publishing of annual accounts.

In other cases, a predictable schedule is disrupted by events. In the United States several years ago, the tampering of Tylenol medicine bottles resulted in consumer deaths. The consequent stakeholder communications were anything but standard and the urgency disrupted a normal timeline.

On the whole, however, the more complex the information and task and the more non-standard or urgent the transaction, the more likely it is that writers will need to use a wider range of evaluation methods on a larger scale.

OUTCOMES

The outcomes criteria are part of the communication requirements but also bridge into business requirements. The first aspect to consider is whether the purpose of a communication is simple or complex. This relates both to the readers’ purpose for using the text and the purpose of the authors to meet a business requirement.

For example, a manufacturer’s purpose for the operating manual of an appliance will be to meet regulatory requirements, to minimise service calls, and to cut manufacturing costs as much as (or more than) to offer consumers an easy-to-use guide. For those consumers, the initial purpose will be to start using the appliance, but then keep the document as a reference for later troubleshooting and service.

The impact of a document also bridges communication and business requirements. It might be low in the case of a routine communication that occurs on a set timeline. But what if the communication is a new warning about the small possibility of a false positive on the charge held by a heart defibrillator? Here the impact on both customer and company may be high because of the risk of death and the possibility of a lawsuit. At the same time, the company does not want to cause panic among its customers, so its purpose is complex.

Overall, the more complex the purpose and the higher the impact, the more types of evaluation may be needed and on a larger scale.

CONTEXT

As we move from communication requirements into business requirements, we begin to consider the sensitivities that should influence evaluation choices for the authoring organisation.

We first must consider the context by mapping the timing and the cost. Timing, like the urgency for the reader, relates to whether the communication is on a standard timeline or is disruptive for the authoring organisation. A disruptive timeline may require further resources in staff time, production, or professional services such as legal advice.

40 The Clarity Journal 76 2018

The costs can flow from timing, but equally from other factors, such as a rise in production costs due to external factors, or the cost of more complex evaluation methods themselves – particularly if the organisation does not have enough internal expertise.

Of course, cost is often cited as one of the main barriers against certain forms of evaluation, such as performance testing. Here, the scalability and range of the framework comes into play. If the budget is limited, the most realistic approach may be an expert review combined with a small number of participants in performance testing. By adjusting the range and the scale of the methods, an organisation can maximize the impact of its available budget. Even with the most negligible (or non- existent) budget, some evaluation is always possible.

RISKS

The final criteria can trump one or all of the others: the level of risk. Too often this aspect is neglected in evaluation decisions. Financial risks are relatively straightforward. Might the organisation experience a financial impact and at what level? Non-financial risks can be harder to measure but are nonetheless real, such as risk to reputation and public confidence.

Let’s consider the case of our defibrillator company. The financial risk to the company from a lawsuit is incredibly high. It may also face high non-financial risk in public reputation and confidence. Even where a communication is simple and for a limited number of people; even if all readers have high literacy and a simple task to complete in response; even if the cost of the right evaluation method is very high and the timing tight, the risks are such that company should invest in evaluation.

3. Using the Kleimann-James evaluation framework

As you were reading these criteria, no doubt many seemed obvious or even common sense. Yet how often do organizations neglect the evaluation of their communications?

In retrospect, for example, would United Airlines have expressed regret about a passenger being physically man-handled off a plane using the term “re-accommodation of passengers”? Would Volkswagen have described its cheating of emissions testing as “possible emissions noncompliance”? And if this happens in high-profile cases with communication crisis teams, how more likely will it be behind the scenes?

For expert practitioners, our framework provides a handy reference to assess what evaluation methods may be appropriate, but also to guide decision makers in adopting expert advice.

To illustrate this more clearly, let’s consider some examples. The first involves a scenario that will lead to more text-focused evaluation, while the second blends a wider range of text- and user-focused methods.

EXAMPLE 1: MEMORANDUM OF ADVICE

In the first scenario, a lawyer in a commercial law firm is preparing a formal memorandum of advice for a corporate client in the mining sector about whether to challenge a recent land classification decision that may affect a proposed extension of the mine’s operations. The lawyer’s advice is that the company should not appeal the classification, as that had limited prospects of success, but should seek an amendment to a development consent with another agency, which will then override the classification.

The advice will be read initially by in-house counsel in the client’s company, then by senior executive staff and Board members who need to approve the company’s response.

The evaluation criteria help to map the requirements for this communication:

Figure 8: Example 1 legal advice

In this case, the document will be read by at most a dozen people, at least initially. And their literacy skills and subject-matter knowledge will be high. Yet the legal issues are complex, so the reader’s task requires effort. And there is a limited time to appeal the classification, so a decision must be made quickly.

Similarly, the impact of the communication is potentially great, as the wrong decision may cost the company millions of dollars. The decision makers will need to balance a range of legal and business outcomes in choosing the right response.

As the situation was unexpected, there is no allocated budget for responding to the situation, including any evaluation costs. But the risks for the company are high, not only in financial terms, but in public reputation if they contest the decision.

Considering these measures as a whole leads to the following evaluation measures (highlighted in bold).

Figure 9: Example 1 evaluation methods chosen

The Reader and Context criteria point toward text-based evaluation methods, not least because of the urgency involved. Yet the Complexity, Outcomes and Risk criteria mean that such methods should be as broad as time permits. The author should draft the advice with reference to a clear standard, but the text should then be subject to expert review by an internal communication specialist.

Yet the risks and impact are such that, even with limited time or budget, some form of user-based evaluation should be considered. In this case, that would likely be a low scale preference test, such as asking two or three colleagues (including non- lawyers) to read the draft advice and evaluate how well they understand and are persuaded by what it is recommending.

Once the communication is sent, outcomes evaluation would be useful to inform future documents of a similar kind. Did the client agree with the advice offered and did that have the right result?

EXAMPLE 2: TERMS AND CONDITIONS

In our second example, a new transport company is attempting to challenge the dominant market player, and it has decided to rewrite its terms and conditions to give it a competitive advantage. The existing competitor has recently been criticised for the poor readability of its terms and conditions. For both companies, the terms and conditions will often be read by users on a mobile device.

Here’s how this scenario scores against the evaluation criteria.

Figure 10: Example 2 terms and conditions

In this scenario, the number of potential readers is relatively large and their literacy skills and knowledge will be average at best. Yet the content and reader task is rather complex, particularly given readers may be reading on a small screen while waiting for a pick up.

While the purpose of the communication is fairly straightforward, it needs to convey information that customers may be surprised about – such as how the company may use personal information. Yet the impact may be high given the purpose to create a commercial advantage and the potential adverse reactions if it does not succeed.

The timing is relatively average, as there have not been any complaints so far about its existing document, and there is virtually no budget for any evaluation. The financial risk is moderately high given the adverse publicity its main competitor has attracted, and the reputational damage that may occur if the company’s own terms and conditions come under similar scrutiny.

This leads to the following evaluation methods (in bold).

Figure 11: Example 2 evaluation methods

Under this scenario, the criteria suggest a much wider range and depth of evaluation methods than in our first example. The evaluation should start with some simple text-based methods, such as calculating the readability scores for the document. But poor results would immediately lead to more detailed expert review by asking one of the firm’s communication specialists to revise the document.

But the reader, complexity, outcomes and risk criteria all point to further evaluation to verify this work. Because the company is looking at strengthening reputation and increasing revenue, it should turn to some user-focus evaluation. This could start by bringing together a small group of fellow workers for an impromptu focus group. If the results show further work is needed, there is now stronger evidence to secure some budget for more formal user-focused evaluation.

This process can evolve progressively, with increasing investment of time and resources until the communication and business requirements are likely to be met. Even if all methods are needed, the timeline is going to be around 3 weeks from start to finish. At that point, the company can finalise some outcome measures. These might include public recognition for a clearer and more transparent document than its major competitor, and, ultimately, increased business and revenue.

4. Conclusions

In both of our examples, evaluation required expertise. It was not a formulaic process that can be automated, and it will still need the judgement of clear communication practitioners. The Kleimann-James evaluation framework provides a structured approach to the communication and business requirements for any text to select the right blend and scale of evaluation methods.

Of course, many practitioners will already work with these criteria and methods. But we have not found a framework that brings them together in a formal way to strengthen evaluation decisions. We also hope our framework will help to explain the importance and feasibility of evaluation in every context, and take our field beyond limiting debates about the absolute value of one method over another.